The Rising Influence of Non-State Actors: Shaping Security Dynamics in Syria and the MENA Region

Written by Abbas Ismail on 01 August 2024

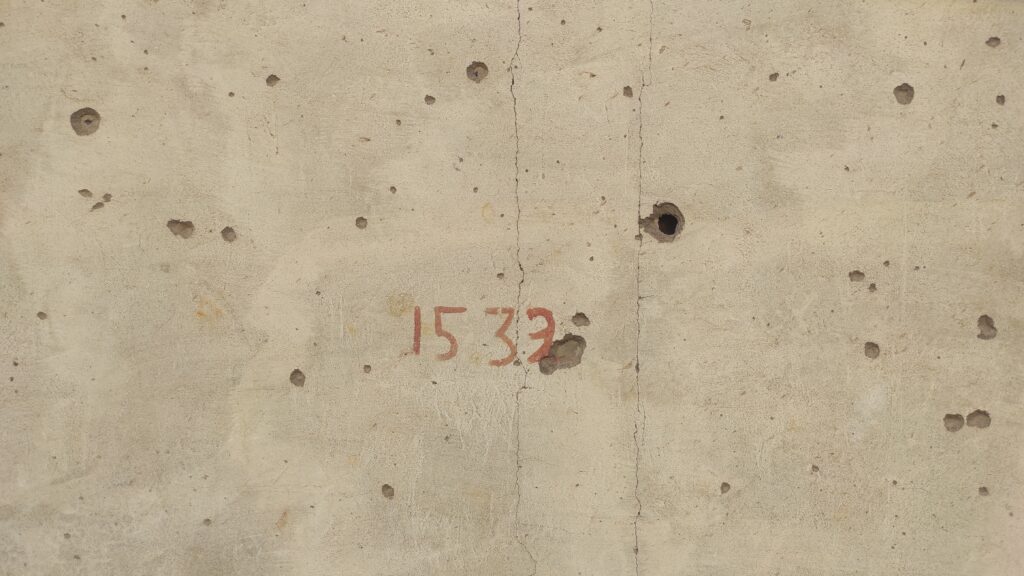

Photo by Abbas Ismail

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region has long been a complex and volatile area, where regional conflicts and shifting alliances create a difficult environment for traditional state actors. Historically, this region has been characterised by geopolitical rivalries, sectarian divisions and the legacy of colonialism, all of which have contributed to ongoing instability. However, the power and conflict dynamics in the MENA region have changed significantly in recent years (Dekel, Boms & Winter, 2016).

The rise of non-state actors – from terrorist organisations and militias to insurgent groups – has fundamentally changed the security landscape. These organisations, which are not bound by national borders or international norms, have taken advantage of the instability in the region to expand their influence and power. They operate outside the control of established governments and fill power gaps left by weakened or collapsing states, further destabilising the region (Dekel, Boms & Winter, 2016). This proliferation of non-state actors has made the already complicated web of conflict in the region even more complex, making the pursuit of peace and stability even more difficult.

Unlike traditional state actors, these groups are often motivated not by national interests but by ideology, sectarian affiliation or financial gain, and employ unconventional tactics, including asymmetric warfare, cyberattacks and information warfare (Baybars-Hawks, 2018). Thanks to their ability to adapt quickly to changing circumstances and the use of modern technology and social media, they are able to recruit, mobilise and operate with remarkable agility (ibid). As a result, these non-state actors have not only become key players in the region’s conflicts, but have also become a significant threat to regional and global security.

Non-State Actors in the Middle East: A Broad Overview

Non-state actors in the MENA region include a broad spectrum of groups with different goals, ideologies and methods. Terrorist organisations such as ISIS and Al-Qaeda have attempted to gain territorial control and impose their extremist ideologies, destabilising entire regions in the process. Meanwhile, groups such as Hezbollah and the Houthis have not only engaged in armed conflicts but have also established considerable political influence, often serving as proxies for external powers such as Iran. These groups often operate in failed or failing states, where weak governance and fragile borders allow them to exert influence over large territories.

The rise and growth of these non-state actors poses a significant threat to regional security. Their sophisticated military capabilities enable them to wage asymmetric warfare that effectively challenges traditional state militaries. In addition, their strategic use of propaganda and social media facilitates the rapid recruitment and spread of their ideologies, amplifying their impact far beyond their immediate areas of operation. The ability of these groups to destabilise governments, disrupt regional economies and incite sectarian violence has become a critical concern for regional and international actors. Their actions not only undermine state sovereignty, but also threaten the broader security architecture of the MENA region, complication efforts to achieve lasting peace and stability.

The Case of Syria: A Microcosm of Regional Challenges

Syria serves as a prime example of how non-state actors can exploit a power vacuum to assert control and influence, fundamentally changing regional security dynamics. Since the outbreak of conflict in 2011, the collapse of centralised authority has transformed Syria into a fragmented battleground for numerous non-state actors, each pursuing their own agenda and often supported by external powers. The initial rise of ISIS, which took advantage of the chaos to conquer vast territories in Syria and Iraq, showed the extreme consequences of such a power vacuum (Dekel, Boms & Winter, 2016). The proclamation of a caliphate by ISIS not only threatened the sovereignty of several states, but also attracted regional and global powers and further destabilised the region.

Even though ISIS has largely been defeated militarily, its remnants continue to pose a significant threat. Operating in sleeper cells and conducting guerrilla-style attacks, the group remains capable of disrupting local security and undermining efforts to stabilize the region. The persistence of ISIS highlights the long-term challenge posed by non-state actors who can adapt to changing circumstances and maintain influence despite territorial losses.

Numerous other armed non-state actors have also emerged in Syria, including less radical Islamist groups such as Ahrar ash-Sham and Jaysh al-Islam as well as pragmatic opposition forces led by the Free Syrian Army. In mid-2014, some opposition groups across Syria managed to unite mainly under the banner of radical Islam, shifting the balance of power somewhat in their favour. In contrast to the regime’s dwindling army, rebel groups, particularly those led by jihadists, have benefited from a steady influx of rotating fighters, including local Syrians and hundreds of foreign volunteers who cross the border every month. Thousands of Hezbollah, Iraqi and Afghan fighters who have joined the fight to support the Assad regime, meanwhile, are struggling to maintain the same level of momentum (Dekel, Boms & Winter, 2016).

Moreover, Non-state actors, such as the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and other various Islamist rebel groups, have also played a central role in the conflict, further complicating regional security. The US-backed SDF have been a major force in the fight against ISIS. However, their ambitions and territorial control have led to clashes with Turkish forces and their allied militias, creating additional layers of conflict within Syria (Rabinovitch & Valesni, 2021). This not only prolongs instability within the country, but also strains relations between regional actors such as Turkey and the United States, each pursuing different strategic objectives in Syria (ibid).

Meanwhile, Islamist groups such as Jabhat al-Nusra (now known as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) have retained control of parts of Idlib province and continue to challenge both the Syrian government and other opposition groups (Bellamy, 2022). Their presence in Idlib, together with the complex web of alliances and enmities between various non-state actors, poses an ongoing threat to any potential peace settlement and keeps the region in a state of constant conflict.

The proliferation of non-state actors in Syria has significant implications for regional security beyond the country’s borders. The involvement of these groups has brought external powers such as Russia, Iran, Turkey and the United States onto the scene, each pursuing their own interests and supporting different factions (Bellamy, 2022). This internationalisation of the conflict has led to a wider regional power struggle in which Syria is the epicentre of competing geopolitical ambitions. The presence of non-state actors is therefore not only destabilising Syria, but also contributing to greater instability across the Middle East, affecting neighbouring countries and creating a security environment characterised by unpredictability and ongoing conflict.

Challenges Posed by Non-State Actors in Syria

The presence of numerous non-state actors in Syria has made the conflict one of the most complicated and enduring crises in the region, with significant implications for regional security (Bellamy, 2022). These groups have created an ever-changing landscape of alliances and enmities. Their ability to rapidly ally with other partners or confront new enemies makes the conflict highly unpredictable and complicates efforts by external powers to engage in effective diplomacy or military intervention. This fluidity of alliances undermines traditional state-based approaches to conflict resolution and often leads to unexpected escalations that further entrench the war.

The involvement of external powers – such as Russia, Iran, Turkey and the United States – has added complexity to the conflict. Each of these states supports different factions in Syria, not only to advance their own strategic interests, but also to counterbalance the influence of other regional and global powers (Rabinovitch & Valensi, 2021). For example, Russia and Iran have supported the Assad regime to maintain their position in the region, while Turkey has focused on fighting Kurdish groups it sees as a threat to its national security (ibid). The United States, on the other hand, has primarily supported the SDF in the fight against ISIS while trying to manage its strained relations with Turkey (Bellamy, 2022). This involvement of external powers has turned Syria into a proxy battleground where local conflicts are exacerbated by broader geopolitical rivalries

Non-state actors in Syria have also demonstrated a high level of sophistication in the use of asymmetric tactics that have significantly affected security in the region. Suicide bombings, improvised explosive devices and targeted assassinations are some of the methods used by these groups to achieve their goals (Baybars-Hawks, 2018). These tactics not only result in significant casualties, but also create an atmosphere of fear and instability that makes it difficult for any authority to gain control. The use of asymmetric warfare has allowed these non-state actors to rise above and effectively challenge both state and non-state adversaries (ibid).

Furthermore, these groups have exploited the fragmentation of Syrian society by exacerbating existing sectarian divisions and creating new ones (Dekel, Boms & Winter, 2016). By aligning themselves with certain ethnic or religious communities, non-state actors have deepened sectarian divisions, making reconciliation and the achievement of lasting peace even more difficult. This deliberate exacerbation of sectarian tensions has spilled over into neighbouring countries, contributing to regional instability and the perpetuation of conflict across borders (Chennoufi, 2022). For example, sectarian strife fuelled by non-state actors in Syria has had a destabilising effect on Lebanon, Iraq and other parts of the region where similar divisions exist.

In addition to their military and ideological activities, non-state actors in Syria are heavily involved in illegal activities such as smuggling, human trafficking and the black market trade in weapons and drugs (Heydemann, 2023). These activities not only provide the financial resources needed to sustain their operations, but also contribute to the further destabilisation of the region. The illicit flow of goods and the exploitation of vulnerable populations contribute to the breakdown of state authority, weakening the economy and exacerbating social tensions. The economic destabilisation caused by these illegal activities creates a vicious circle in which poverty and lawlessness encourage the recruitment of non-state groups and perpetuate the conflict (Heydemann, 2023).

The entrenchment of the non-state actors in the Syrian conflict has turned the country into a hub of regional instability, the consequences of which are felt far beyond Syria’s borders. For regional and international actors, dealing with the threat posed by these non-state actors requires a multifaceted approach that goes beyond military intervention and also focuses on diplomatic engagement, economic stabilisation and efforts to bridge sectarian divides.

Addressing the Challenge: Strategic Responses

To effectively address the challenge posed by non-state actors in Syria and the MENA region as a whole, a comprehensive and multi-layered approach is essential, as these groups are deeply embedded in the socio-political fabric of the region. A key element of this strategy is to improve intelligence collection and sharing, which is critical to understanding the structure, tactics and motivations of non-state actors. Accurate and timely intelligence is critical to anticipating the actions of these groups and formulating effective countermeasures. This requires not only co-operation between military and civilian analysts, but also solid partnerships between regional and international actors. The framework for intelligence sharing needs to be strengthened to ensure a seamless flow of information between those involved in countering these threats, enabling coordinated responses that are more likely to be successful.

The integration of a networked economic system has significant consequences for any post-conflict transition. Non-state actors are often faced with uncertainty about their long-term survival. However, as Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s approach to economic governance increasingly aligns with that of non-state armed groups, the likelihood that these actors will continue to exist after a solution that restores regime control over contested regions increases. A settlement that does not address the underlying systemic and structural criminality is likely to have minimal impact on improving social, economic and security conditions for the civilian population (Heydemann, 2023).

Therefore, to intelligence and military intervention, it is essential to tackle the root causes that give rise to non-state actors in the first place. Problems such as poverty, unemployment and political disenfranchisement provide fertile ground for these groups to recruit and gain support. In regions where governance is weak or non-existent, non-state actors often step in to fill the gap by providing services, security and a sense of identity that the state cannot offer (Dekel, Boms & Winter, 2016). Therefore, strengthening governance structures is critical to restoring state authority and legitimacy. This includes promoting inclusive political processes that give voice to marginalised communities and thus reduce the grievances that non-state actors exploit.

Moreover, the reconstruction of war-torn societies must be a priority. In Syria and other parts of the MENA region, years of conflict have destroyed infrastructure, displaced millions of people and shattered social cohesion. Rebuilding these societies requires not only physical reconstruction, but also efforts to overcome divisions and promote national unity (Mani, 2005). International support, both in the form of financial assistance and expertise, is crucial to these reconstruction efforts (Asseburg, 2020). Rebuilding a functioning state apparatus that can provide basic services and ensure security is key to reducing the influence of non-state actors.

From a regional security perspective, addressing the challenge posed by non-state actors in Syria is not just about stabilising one country, but about securing the entire MENA region. The spillover effects of the Syrian conflict, including the spread of extremism, the displacement of refugees and the destabilisation of neighbouring countries, make it clear that security in the region is interconnected. Therefore, efforts to counter non-state actors must also take into account the regional context, with coordinated strategies that address cross-border threats and promote stability across the MENA region.

Conclusion

The evolving dynamics in the MENA region, exemplified by the situation in Syria, reveal the profound influence of non-state actors on regional security. These groups – from terrorist organisations such as ISIS to various militant and opposition factions – have dramatically altered the landscape of conflict by exploiting power gaps, manipulating sectarian divisions and engaging in asymmetric warfare. Their actions have not only destabilised Syria, but have also had far-reaching consequences for neighbouring countries and the entire MENA region.

The Syrian conflict has become a microcosm of the wider regional instability, highlighting the complex interplay between local and international actors. Non-state groups have skilfully used modern technology, social media and unconventional tactics to advance their goals, complicating efforts to restore order and peace. Their involvement has turned Syria into a battleground for competing geopolitical interests, with external powers such as Russia, Iran, Turkey and the United States each supporting different factions, exacerbating the conflict and prolonging instability.

Addressing the challenges posed by non-state actors requires a multifaceted approach that goes beyond traditional military solutions. Effective strategies must include robust intelligence gathering and sharing, co-operative regional and international partnerships, and a focus on the root causes of instability such as poverty, political disenfranchisement and weak governance. In addition, post-conflict reconstruction and governance reforms are critical to restoring state authority and legitimacy, while efforts to address cross-border threats and regional instability will be crucial to achieving long-term stability in the MENA region.

Ultimately, the security of Syria and the entire MENA region is interlinked, requiring a holistic approach that integrates intelligence, military, political, and developmental strategies to the threats posed by non-state actors. Only by addressing both the immediate and underlying causes of instability and strengthening state institutions can the power of these groups be effectively diminished, paving the way for long-term peace and security in the region.

References

Asseburg , M. (2020). Reconstruction in Syria: Challenges and Policy Options for the EU and its Member States. SWP Research Paper 2020/RP 11. https://doi.org/doi:10.18449/2020RP11

Baybars-Hawks, B. (2018). Non-state actors in conflicts: Conspiracies, myths, and practices. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Bellamy, A. J. (2022). Syria Betrayed: Atrocities, War, and the Failure of International Diplomacy. Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/bell19296

Chennoufi, M. (2020). Identité politique, structure de conflit, et médiation. Études internationales, 51(2), 339–361. https://doi.org/10.7202/1084462ar

Dekel, U., Boms, N., & Winter, O. (2016). The Rise of the Non-State Actors in Syria: Regional and Global Perspectives. In Syria’s New Map and New Actors: Challenges and Opportunities for Israel (pp. 13–24). Institute for National Security Studies. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep17013.5

Heydemann, S. (2023). Syria’s dissolving line between state and nonstate actors. Nonstate Armed Actors and Illicit Economies in 2023” from Brookings’s Initiative on Nonstate Armed Actors. https://doi.org/https://www.brookings.edu/articles/syrias-dissolving-line-between-state-and-nonstate-actors/

Mani, R. (2005). Rebuilding an Inclusive Political Community After War. Security Dialogue, 36(4), 511–526. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26298951

Rabinovich, I., & Valensi, C. (2022). Syrian Requiem: The Civil War And Its Aftermath. Princeton Univ Press. ISBN 9780691212616 (ebook)